Picture Stories. Portraits of Munich Jews

A boy in a sailor suit, a lady in a beret and with huge puffed sleeves, a rabbi with an open…

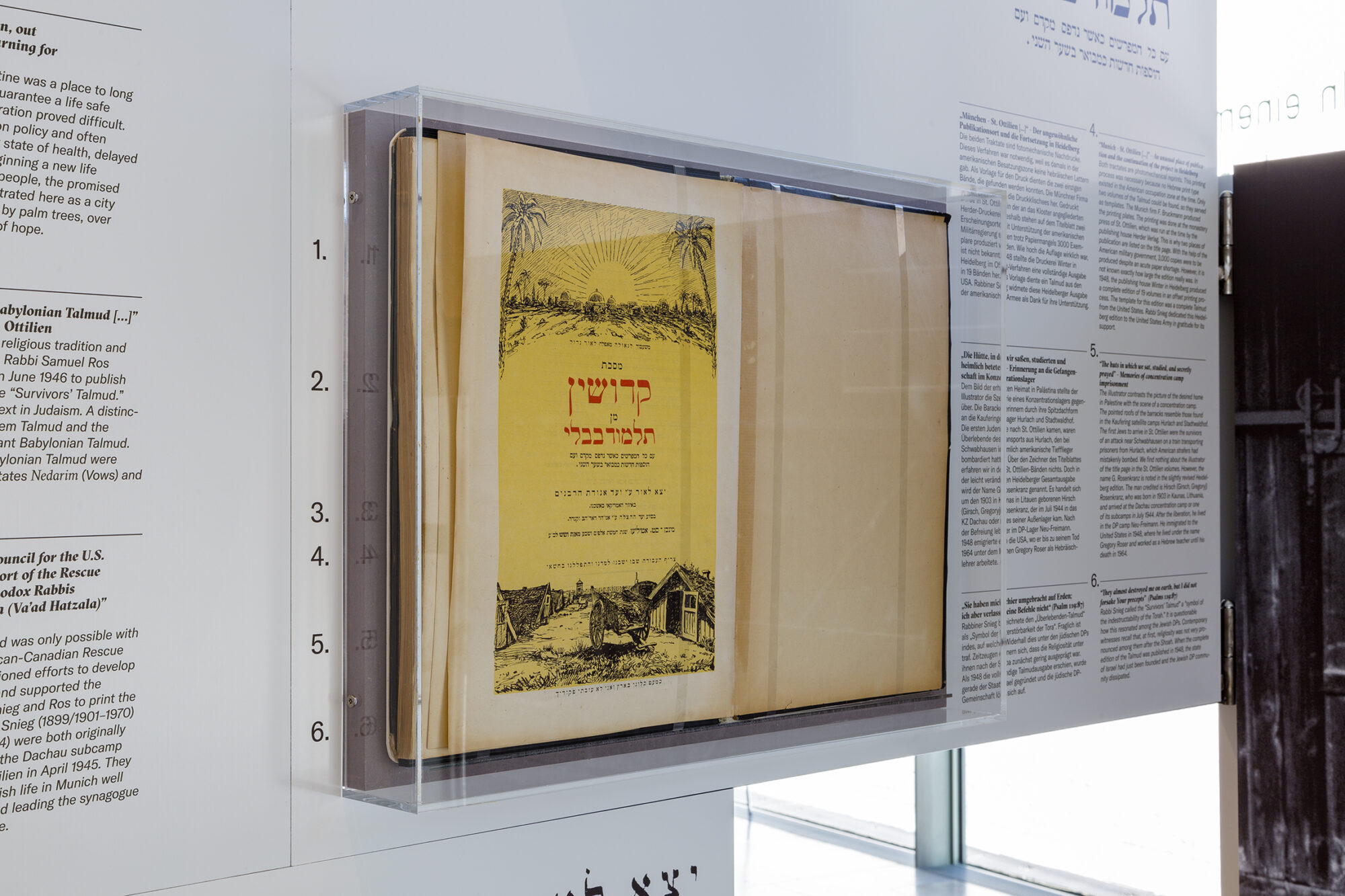

The Benedictine monastery and its Jewish history 1945–48

A project by the Institute of Jewish History and Culture, History Department, Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU), St. Ottilien Archabbey, and the Jewish Museum Munich.

The Yiddish poet Leivick Halpern (known as H. Leivick) wrote that Jewish children and the sound of church bells greeted him upon his arrival at St. Ottilien in the spring of 1946. Between the years 1945 and 1948, the monastery of the Missionary Benedictines was an involuntary destination for more than 5,000 Jewish survivors from Eastern Europe. Behind these people lay the atrocious experiences of the Shoah, ahead of them an uncertain future. St. Ottilien offered them an idyllic setting, well-equipped medical facilities, and an adequate supply of food produced by its own farmlands. It became a place to convalesce and recuperate, but also to wait and hope. The three-year history of the Jewish presence at the Catholic monastery began in late April 1945 when the Allies bombed what they thought was a German military transport train that, unbeknownst to them, was full of trapped Jewish concentration camp prisoners being shipped from the Kaufering satellite camps. The injured survivors of that attack were brought to the German military hospital that had existed at St. Ottilien since 1941, where about a thousand German soldiers were also being treated at the time.

Civilians who found themselves outside their home countries because of the war were labeled Displaced Persons (DP) by the Allied armed forces. Gradually, St. Ottilien developed into a Jewish DP hospital that in cluded a DP camp and a maternity ward, in which more than 400 Jewish children were born. The patients and convalescents were under the care of German doctors and nurses, nuns and monks, and also an increasing number of Jewish caregivers. The survivors quickly set up the institutional structures, conducted primarily in Yiddish, that were needed for everyday life: a prayer room, a kindergarten and yeshiva, a kosher kitchen, athletic and chess clubs, occupational training courses, and political parties. The camp orchestra of St. Ottilien became famous and performed at the DP camps throughout the American occupational zone. At the same time, the first medical director of the hospital, Dr. Zalman Grinberg, became one of the leading figures of the Jewish self-administration in Bavaria.

In the summer of 1945, the monastery, which the National Socialists had confiscated years before, was turned back over to the Benedictine Order. Gradually, monks returned from their forced labor and military service assignments. But the situation that they faced upon their return was not an easy one: housing was in short supply and exercising religious duties was difficult to the point that conflict with the American military government, Jewish self-administration, and international relief organizations became nearly inevitable.

This unique time immediately after the war was characterized by the encounter of religions, the interaction between the Jewish DPs and the local German population, and the rhythm of daily life at the DP hospital and camp. Until now, this has been a littleknown chapter in the history of the monastery, but in 2018 it is the focus of a varied program of activities.

Conception und realization: Evita Wiecki (LMU), Jutta Fleckenstein (Jüdisches Museum München), Pater Cyrill Schäfer (Erzabtei Sankt Ottilien)

Exhibition Architecture: Lendler Ausstellungsarchitektur, Berlin