AEJM

AEJM

Words of Farewell and Orbituaries to Bernhard Purin

In this article, we publish words of farewell and obituaries for our esteemed colleague Bernhard Purin. Bernhard, the sentence that always…

The Jewish Museum in Prague is pleased to announce that measures taken by the Israeli Police, the Czech Police and Interpol led to the successful completion of the process of returning a fragment of a rare Hebrew manuscript – the Pinkas of the Kyjov/Gaya Jewish Community, dating from 1654-1854, which was stolen from the archive collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague on the 30th of January 2007. The fragment of the rare manuscript travelled back to the Czech Republic with the help of the Embassy of the Czech Republic to the State of Israel and was personally handed over to the museum’s director Mr Leo Pavlát by the Czech ambassador to the State of Israel Mr Ivo Schwarz.

Pinkas (also called Pinkas ha-kehilot, pl. Pinkasei ha-kehilot) is a Hebrew term for a hand-written volume with information on Ashkenazi Jewish communities in Europe. Such community books usually contain official records and are an irreplaceable source for the study of individual Jewish communities and their demographic development. In its entirety, the Pinkas in question is a unique source of information on the development and life of the Jewish community in Kyjov/Gaya and its environs in the two hundred-year period between 1654 and 1854. For this reason, its value is incalculable.

Missing for several years and registered in Interpol’s database of stolen artworks, the manuscript in question was found to be in the online catalogue of the Israeli auction house Asufa – a discovery made by experts at the Jewish Museum on the 4th of January 2015. After verifying all the necessary details and making sure that it was the actual manuscript in question, the Jewish Museum immediately asked the auction house to withdraw the item from sale and to return it promptly, having proved its ownership claim and shown that it was the missing item in question, the theft of which was recorded in Interpol’s database. At the same time, the Jewish Museum informed the Czech Police of its discovery and requested that it notify Interpol of this fact and contact their Israeli colleagues for co-operation in securing the manuscript.

Out of fear of delay, the Jewish Museum entered into parallel negotiations with the Asufa House of Auction and with the vendor’s legal representative. In connection with this, it became apparent that only part of the stolen manuscript was on offer at the auction. The thieves had evidently removed the manuscript from its original leather binding. There are various reasons for handling such a rare volume in this way – for example, in expectation of getting more money from selling it in parts, or as an attempt to make it more difficult to identify the item when put to auction.

From the outset, the vendor of the manuscript was unwilling to accept the Jewish Museum’s request to return the item in question, repeatedly arguing that the item in question was not the one that had been stolen. As a consequence, experts at the Jewish Museum had to prove that it was in fact a fragment of the stolen volume. As there is a complete copy of the manuscript at the Jewish Museum and as there is a complete microfilm copy of the manuscript at the Hebrew National Library in Jerusalem, it was possible to clearly show that the folios of the Prague manuscript and the folios of the fragment on offer at the Asufa auction are identical in the smallest of details, including the lettering anomalies, irregularities, extent of damage, and earlier restoration measures.

The theft of a manuscript from the Jewish Museum in Prague since it regained its independence from the state in 1989 is a rare occurrence, but there were a number of losses from its collections between 1942 and 1989. There were cases when objects were illegally removed from its collections and sent abroad, for the most part in the period between 1945 and 1989. Considering the historical circumstances under which the Jewish Museum’s collections came into being – nearly all of the movable cultural property of Jewish communities, associations and corporations in what was then the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was shipped to the museum between 1942 and 1945 – it is likely that pieces of Judaica of Bohemian provenance that are currently available in the current art market may actually be missing items that rightfully belong to the Federation of Jewish Communities in the Czech Republic, which is represented by the Jewish Museum in Prague.

Anyone who owns or is considering to purchase a piece of Judaica from Bohemia or Moravia, or who is to receive such an item as a gift or bequest, should therefore be very cautious and ensure through all possible means that the item in question is not missing from one of the Jewish Museum’s famous collections. The Jewish Museum in Prague is willing, free of charge, to check the provenance of any piece of Judaica originating from Bohemia or Moravia. This will relieve any prospective vendor or buyer of unnecessary worries and risks.

Photo: Jewish Musum in Prague

AEJM

AEJM

In this article, we publish words of farewell and obituaries for our esteemed colleague Bernhard Purin. Bernhard, the sentence that always…

AEJM

AEJM

The Association of European Jewish Museums is deeply saddened about the passing of Lord Jacob Rothschild Z”L, a true philanthropist whose…

AEJM

AEJM

We received the shocking news of the passing, last week, of our esteemed colleague Bernhard Purin. Two of his closest colleagues,…

AEJM

AEJM

The AEJM Board wants to express its solidarity for our board member, Prof. Dr. Mirjam Wenzel, Director of the Jewish Museum…

AEJM

AEJM

For the complete 01/2024 Newsletter, click here Dear Friends of the AEJM, Dear Colleagues, In the first issue of our Newsletter…

AEJM

AEJM

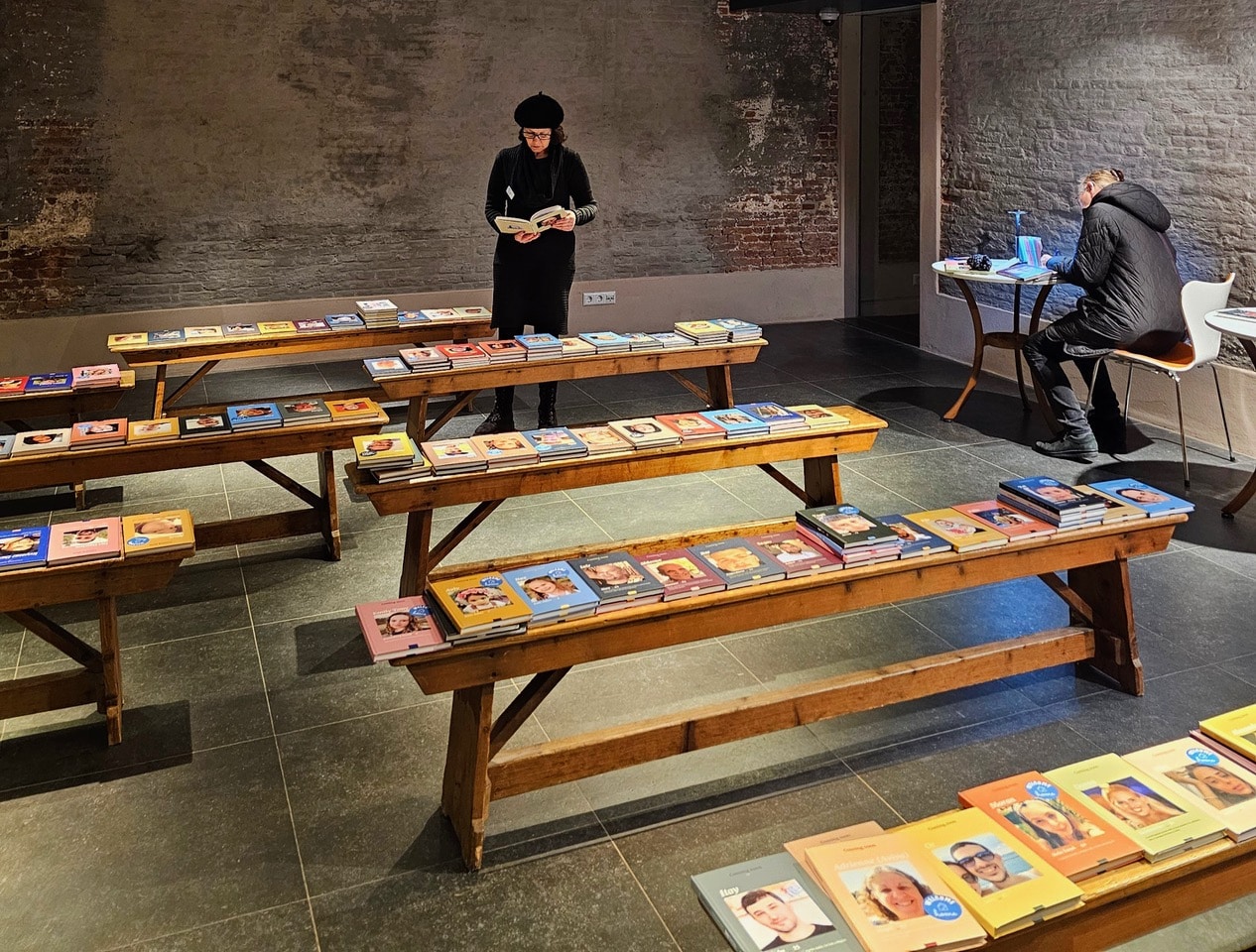

In each breath, they are with us. Indelible parts of the whole. Each of them has a story. Open their book….